Pope Adrian VI, the ‘Barbarian From the North’ Who Wanted to Reform the Vatican

Five hundred years ago, Adrianus of Utrecht was unexpectedly elected pope. The ambitions of the Netherlands’ first and only pope in history were great. He wanted to reform the administration of the Vatican, but his untimely death put an end to his plans. His pontificate lasted barely twenty months, yet he is much more than a footnote to history.

In the first week of 1522, a conclave of thirty-nine, mostly Italian, cardinals in the Sistine Chapel were unable to agree on a successor to replace the recently deceased Pope Leo X. The conclave had become a geopolitical chess game between the German and French factions, meaning none of the candidates could count on a two-thirds majority. It was during the eleventh ballot, on 9 January, that Cardinal de’ Medici proposed Adrianus of Utrecht, a cardinal who did not even live in Rome. ‘He is a venerable man of sixty-three years, and widely known for his piety,’ said Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici. And then, ‘as by a miracle of the Holy Spirit,’ everyone suddenly rallied behind the absent candidate, Cardinal Adrianus of Utrecht.

Pope Adrian VI (1459-1523), after Jan van Scorel, c. 1625, Centraal Museum, Utrecht

Pope Adrian VI (1459-1523), after Jan van Scorel, c. 1625, Centraal Museum, Utrecht© Wikipedia

The cardinal was actually in Spain at that moment, so the news of his appointment only reached him weeks later in the Basque town of Vitoria, where he, as a governor in the service of Emperor Charles V, was preparing for a confrontation with the army of the French king. Allegedly, Adrianus sighed deeply when he heard the news. ‘If this is true, have mercy on me!’ After years of clashing arms in the service of the Emperor, his greatest desire was to return to the tranquillity of his native city of Utrecht. But divine providence had ordained otherwise. ‘Probably everyone is very surprised at the unanimous choice of someone so poor, so unknown and as far away as I am,’ Adrianus wrote to a compatriot. An old friend, Desiderius Erasmus, congratulated the new pope, saying: ‘The Christian world is miserably torn apart by the deadly conflict of sects and schisms. The whole world looks only to you, Adrianus, as the man who can restore peace to mankind.’

But why was Adrianus the only pope the Low Countries has ever produced? How did this citizen’s son end up in that European centre of power, the Vatican?

The coronation of Pope Adrian VI, depicted on a lantern console in his native city Utrecht

The coronation of Pope Adrian VI, depicted on a lantern console in his native city Utrecht© Wikipedia

Adriaan Floriszoon was born on 2 March 1459 in Utrecht, the son of a well-to-do ship’s carpenter. He attended the Latin school of the Brothers of the Common Life, probably in Zwolle, where he became acquainted with the simple seriousness of Modern Devotion, a religious movement that had originated in the fourteenth century in the Dutch towns located along the river IJssel. Its adherents strove to live godly and conscientious lives in imitation of Christ. The impressions Adrianus gained here influenced his whole life and sowed the seeds for his zeal to reform. At age 17, he went to the university in Leuven (Louvain) as a theology student and quickly gained a reputation as a scientist, eventually becoming rector of the university and dean of the city.

Statue of Adrian VI in L'Ampolla, Spain

Statue of Adrian VI in L'Ampolla, Spain© Angelique Rijken-Hetzler

In 1507 Emperor Maximilian of Austria appointed Adrian as a tutor for his grandson, Prince Charles of Habsburg. At the end of 1515, Maximilian sent Adrian to Spain to secure the crown of Castile for him. Adrian was appointed Bishop of Tortosa, then Cardinal and Grand Inquisitor. It was when Charlemagne was crowned emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation in 1520 that he appointed Adrian as his deputy in Spain.

After receiving news of his election in January 1522, it took Adrian more than half a year to cross the Ebro Valley to the Spanish coast and sail through the Mediterranean to Rome. He arrived as a stranger and the Italians seemed immediately to regret their choice. They were not expecting such a ‘barbarian from the North.

Two burning issues were close to the Dutch pope’s heart when he was finally crowned in St. Peter’s Basilica on 31 August 1522. First, he wanted to unite the European monarchs in a crusade against the Muslim armies of Sultan Süleyman, who was threatening Hungary and Rhodes.

Coat of arms of Pope Adrian VI

Coat of arms of Pope Adrian VI© Wikipedia

He also wanted to reform the administration of the Vatican – the Roman Curia – because, in his view, that is where the diseases of the church had originated, so that is where the healing had to start. Upon his accession to the papacy, he admonished his cardinals in the words of Saint Bernard: ‘He who is covered with sin can no longer smell the stench of filth.’ He called on them to live frugally and only for the good of the Church and the world. With this admonition, Adrian was also hoping to take the wind out of the sails of the rebellious monk Martin Luther. Luther, by posting his indulgences five years earlier, had unleashed a revolt against the corrupt clerical elite in Wittenberg, Germany and was working towards an outright schism with the Mother Church of Rome.

The new pope reluctantly relocated to the luxurious apartments of the Apostolic Palace but his daily life still followed the rhythm of the monastic orders of the time. Soon, the Italians began to complain that the Vatican was becoming a silent monastery. There was an exodus of artists and writers who neither shared Adrian’s urge to reform nor benefited from his lack of money.

Coin with image of Pope Adrian VI

Coin with image of Pope Adrian VI© Wikipedia

During the year that Pope Adrian VI resided in the Vatican, few of his reforms actually came to fruition. He was, for example, unable to stem the trade in clerical offices. The Italian opposition was too strong, and the time too tight. In the spring of 1523, at the Diet of Nuremberg, he publicly apologised to the German princes and prelates for the many illnesses and sins of his church, but that was not enough to get Luther on his side. Luther insulted Adrian, calling him a Leuven pope’s lackey. Adrian begged his old, and more eloquent, friend Erasmus to come to Rome to support him in his war of words with the reformers, but Erasmus preferred not to stick his hands in this ‘wasp’s nest’. An even greater disappointment for Adrian was his inability to unite the Christian princes against the Sultan’s Turkish armies.

After a pontificate of barely twenty months, Adrian VI died on 14 September 1523. Poison was immediately suspected but, in fact, he probably succumbed to the stress of his office and died of blood poisoning. The Roman faction was relieved, happy that they were freed from this ‘Fiammingo, mai non visto e senza nome’ – the Fleming whom no one had ever seen and of whom no one had ever heard.’ It was not until 1978 that another non-Italian would be elected pope: the Pole, Karol Wojtyla.

Tomb of Adrian VI in the Santa Maria dell'Anima in Rome

Tomb of Adrian VI in the Santa Maria dell'Anima in Rome© Wikipedia

Adrian has often been regarded as little more than a footnote between two Renaissance popes, Leo X and Clement VII. But five centuries later there is still some appreciation for his passionate efforts to reform the Church of Rome. Many of the changes that the Dutch pope had campaigned for in vain were finally implemented decades after his death at the Council of Trent, which began in 1545 as a Catholic response to Luther. Because of the significant role played by his kindred theological spirits from Leuven at the council, Adrian has sometimes been called the first pope of the Counter-Reformation. The current Pope Francis revealed shortly after his own inauguration in 2013 that he was considering naming himself after the only Pope from the Low Countries, ‘because Adrian VI was a reformer and reform is needed.’

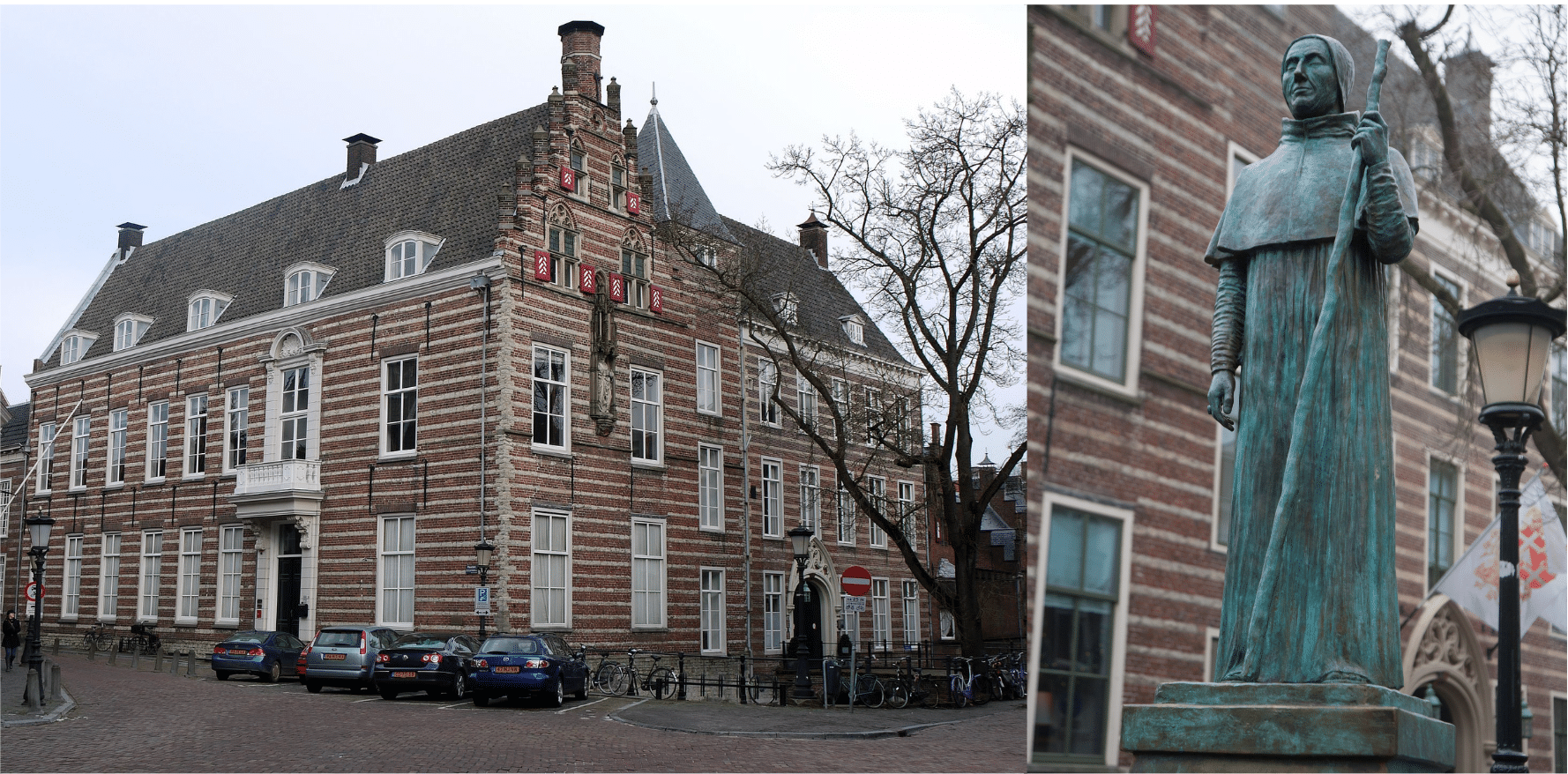

Statue of Pope Adian VI next to the Paushuize (Pope's house) in Utrecht

Statue of Pope Adian VI next to the Paushuize (Pope's house) in Utrecht© Wikipedia

Adrian’s most tangible legacy can now be found in two monumental buildings that he himself never saw. In 1517 he had a distinguished residence built in Utrecht – known today as the Paushuize (Pope’s house) – in preparation for his return from Spain. In his will, he arranged for the construction of the Pope’s College on the Hogeschoolplein in Leuven as accommodation for impoverished theology students. The nearly 200 students who now live there call themselves the Papists and run their own Pausbar (Pope Bar).

Entrance of the Pope's College in Leuven

Entrance of the Pope's College in Leuven© Twan Geurts